Filmed almost entirely in Google Earth, On Exactitude in Science is a three-part video work melding fact and fiction, archive and allegory into a speculative documentary about the rise of digital mapmaking among technology companies.

The series is named after Jorge Luis Borges’s famed short story about an empire’s failed attempt to build a map “whose size was that of the Empire, and which coincided point for point with it.” By the end of the story, a younger generation has deemed the 1:1 map impractical and abandoned both map—and by, implication, empire—to the elements.

Although Borges’s fiction was published in 1946, his insights remain relevant in thinking about digital mapmaking today. As the historian Jerry Brotton observes in his history of mapmaking, Google differs remarkably from previous mapmakers. Much like the empire in Borges’s story, Google Maps and Earth dominate global mapping on a historically unprecedented scale, imposing a “singular geospatial version of the world in an act of cyber-imperialism” with secret algorithms and codes rather than publicly available sources and techniques. Moreover, while previous mapmakers certainly had commercial motives, Google and its rivals like Apple are the only mapmakers whose motives are exclusively profit-oriented.

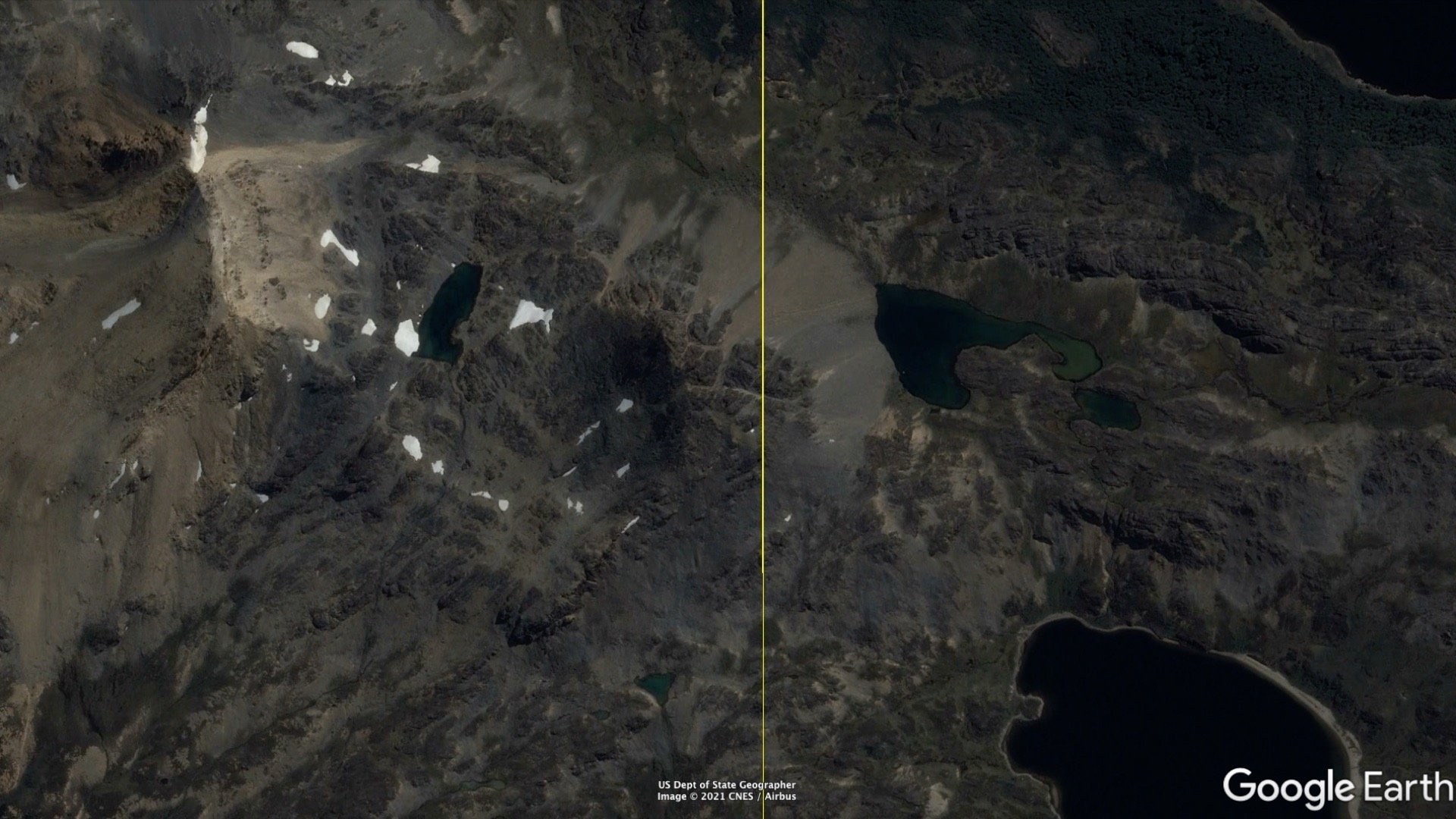

Unlike even the 1:1 map in Borges’s tale, Google Earth seemingly leaves no dimension unrepresented. Users can fly through the air, swim undersea, zoom out to view the solar system, or zoom in on details only visible aerially. They can toggle historical layers to view the past and are guided to an overly determined future via Google’s constantly updating directions and recommendations. When a restaurant appears prominently in Google Maps, we become more likely to eat there. When Google predicts heavy traffic, we take an alternate route. Similarly, when Google erroneously shifted a border between Nicaragua and Costa Rica in 2010, the two countries nearly went to war.

Narrated by an AI speech synthesizer whose style and tone match that of Borges’s fictional chronicler, my video revives Borges’s classic map-territory fable for the digital age in a loose allegory of Google Earth and Maps: their conception in 2005, their rise to global dominance over the next decade, and their involvement in the 2010 Nicaragua-Costa Rica border dispute. Along the way, the video traces Google's involvement in diplomacy, trade relations, policing, and surveillance, raising critical questions about the implications for privacy, sovereignty, and the control of public information and space.

As the British statistician George Box famously noted, “Essentially, all models are wrong, but some are useful.” Yes, but to whom and for what purpose is the wrong model useful? Whom does the scaling serve and why? How might we develop new models that serve the public interest?

My video elaborates on these questions while rejecting the traditional documentary’s claims to truth or “exactitude in science,” claims that too closely mirror Google’s own universalizing data aesthetics. In staging fantastical, darkly comic scenes within Google Earth, the work fractures Google's hegemonic cartography, inviting audiences to imagine unmappable interiorities, unplottable coordinates, and other new scales of resistance.